In his chapter “Manufacturing: Lowering Boundaries, Improving Productivity” from the book The Economic Payoff from the Internet Revolution: Brookings Task Force on the Internet, HBS professor Andrew McAfee, discusses how the Internet has increased manufacturing productivity, lowered costs, and enabled businesses to form mutually beneficial alliances.

Once two or more companies agree to do business with each other on activities beyond simple procurement, they again face a challenge in executing many joint processes as efficiently as possible. In addition, these processes are typically less well defined in advance than those of the procurement cycle; there is, therefore, the added challenge of process definition before automation can take place. At present, Internet technologies are being widely deployed to meet these twin challenges—to build rich point-to-point links between alliance partners and to enable communities of manufacturers to work in harmony.

Point-to-point Links

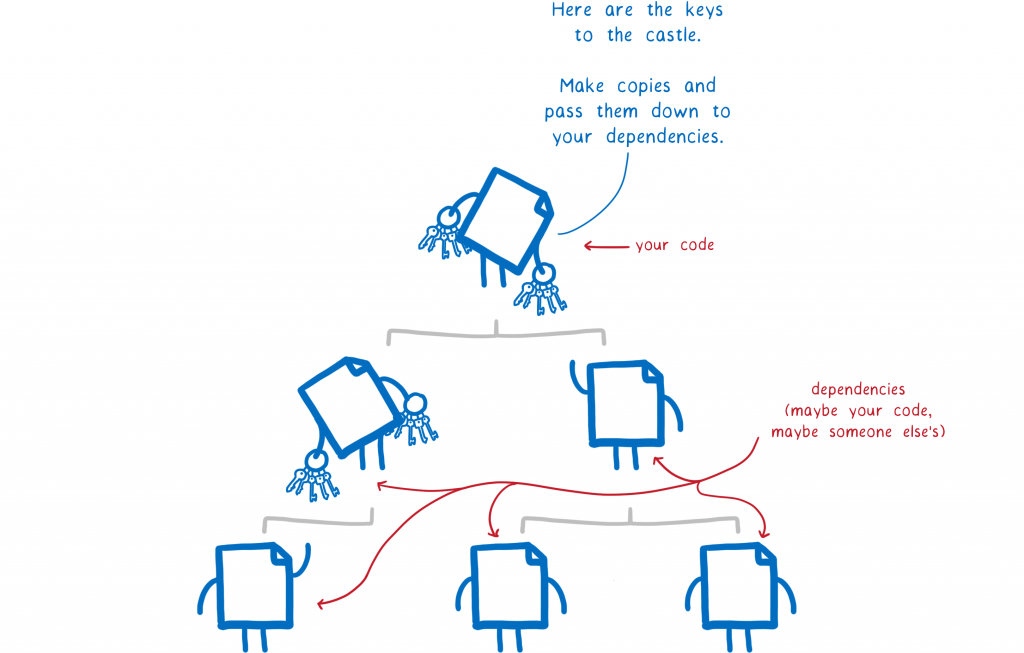

The most obvious intercompany use of the Internet is probably construction of a point-to-point link between two alliance partners. These are companies that have agreed to do a substantial amount of business together and so are willing to invest resources in building a highly functional link, especially one that allows their information systems to interact on routine tasks without human intervention. This intervention is costly and can slow down necessary activities. However, it is also currently widespread; in a survey of fifty global manufacturing companies, 62 percent reported that they used primarily manual methods to share production schedules with their partners, with one respondent stating, “Our biggest coordination headaches come from a lack of visibility into our suppliers’ systems. That translates into long and inconsistent lead times.”

Multi-partner Integration

In addition to enabling rich point-to-point links, the Internet is also being used to integrate groups of alliance partners, just as it is being employed to unite dispersed functional or geographic groups within a firm. While automatic process execution continues to be valuable for these networks, the greater goal of integration often appears to be better and faster decision making. For example, current versions of supply chain management and advanced planning and scheduling software embed more advanced algorithms than their predecessors and offer the possibility of optimizing decisions across an entire supply chain, as opposed to within single firms. To do this effectively, this software obviously requires accurate concurrent data from all members of the supply chain, and the Internet-based technologies discussed above are rapidly proving to be the preferred channels for these data.

Process Consortia

Manufacturers in many industries, realizing that their interactions are far from efficient, are exploring ways to improve. The U.S. high-tech manufacturing community is perhaps furthest along with this effort; it has created a consortium called RosettaNet to develop standards at all required levels—from XML data formats to interaction scripts (called “partner interaction processes”)—to enable productive automatic interactions. To understand the goals of this effort, and the extent of current difficulties (even in this relatively IT-enabled industry), it is worth quoting extensively from the RosettaNet website’s Executive Overview:

The electronic components (EC) and information technology (IT) industries remain infinitely focused on creating and selling the next generation of our fast changing technologies, and thus we have not taken the time, effort, or collective resolve to develop a set of industry-wide electronic business interoperability standards. Given the deep changes exacted by the new digital economy, coupled with the growing size of the EC and IT sectors within the overall economy, we can no longer afford to further postpone attention to efficient business process interfaces between supply-chain trading partners.

The lack of electronic business interfaces in the EC and IT supply chains puts a huge burden on manufacturers, distributors, resellers, and end-users, ultimately creating tremendous inefficiencies and inhibiting our ability to leverage the Internet as a business-to-business commerce tool. Here are a few examples:

Manufacturers today utilize complex processes to all but guess inventory levels and locations across the supply chain at any point in time. This is because there is no agreement on something as simple as how a part number is defined or how inventory queries can be made through a standard interface. This significantly impacts production planning, channel allocation, and the cost of returns.

Distributors, who provide pre- and post-sale technical support to their resellers on tens of thousands of SKUs, must grapple with disparate forms of product information collected from hundreds of manufacturers with no common taxonomy. The lack of product information standards makes the current aggregation and dissemination of such content an expensive and inefficient proposition—an effort duplicated by each distributor in the channel. This problem is further compounded by content’s explosive rate of change.